Analysis from The Economist:

http://www.economist.com/news/middle-east-and-africa/21696951-long-fight-retake-iraqs-second-biggest-city-mosul-has-begun-last

Islamic State in Iraq

The last battle

The long fight to retake Iraq’s second-biggest city, Mosul, has begun

--

IT WAS not an auspicious start. On March 24th the government in Baghdad announced the beginning of operations to retake the city of Mosul, Iraq’s second largest, from Islamic State (IS). The first phase went well. An Iraqi force of about 5,000 quickly overran several villages. But within a few days progress stalled, when a counter-attack by no more than 200 IS fighters resulted in the loss of the village of al-Nasr and the high ground it sits on. Some 20 Iraqi soldiers were killed. An American marine also died from a rocket attack on a small American “fire base”, established to provide artillery support, an indication of America’s expanding role in the conflict.

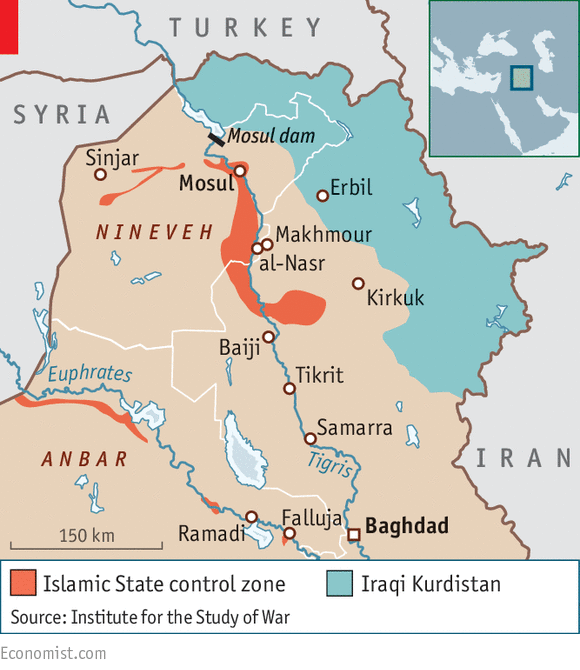

Iraqi officials still talk positively about pushing IS out of Mosul before the end of the year. It is a big prize: the mainly Sunni Arab city had a population of 2m when it fell to IS in June 2014, and is the key to regaining control of the northern province of Nineveh. But the setback at al-Nasr has been a reality check. Just to take and hold al-Nasr, the local operations command says it needs to bring in more tribal fighters and police.

Military analysts reckon there is, in fact, little prospect of a concerted attempt to regain Mosul before 2017. Michael Pregent, a former Intelligence Officer who served as an adviser to Kurdish peshmerga fighters in 2005-06 and worked with Sons of Iraq during the 2007 surge (and is now at the Hudson Institute, a think-tank), says no force large enough to do the job has been built. One under-strength Iraqi division with some American military advisers will not cut it. Pentagon sources reckon that a force of at least 40,000 will be needed.

The problems do indeed appear immense. Iraqi intelligence puts IS’s fighting strength in Mosul at around 10,000, although the Americans think that the number is dwindling as IS comes under pressure elsewhere. Whatever the precise figure, IS has had the best part of two years to build multilayered defences. Mr Pregent says that although there are reasonably capable peshmerga forces to the east of Mosul that can help, these units have little interest in trying to take a city that will never be a part of Kurdistan and in which their presence would provoke ethnic tensions.

The Shia question

The same concerns, only more so, apply to the Shia-dominated Hashd al-Shaabi, or Popular Mobilisation Units. Their leaders claim that it will be impossible to regain control of Mosul unless they are involved. However, when Iraqi security forces (ISF) drove IS out of Ramadi, the capital of largely Sunni Anbar province, earlier this year, the Baghdad government, under pressure from the Americans, ordered the Hashd, some of which are trained by Iran, to stay away. They did not want a repeat of the sectarian reprisals that marred the retaking of another Sunni city, Tikrit, last year.

There are other risks in deploying the Hashd for the assault on Mosul. In a survey carried out in February by an Iraqi polling firm that included 120 respondents in Mosul, 74% said they did not want to be liberated by the mainly Shia Iraqi army on its own, while 100% said they did not want to be liberated by Shia militias or Kurds. That does not mean Mosul’s inhabitants support IS—according to a nationwide survey in January, 95% of Iraqi Sunnis oppose it—but it does suggest that they are at least as fearful of their potential liberators as they are of their oppressors. One solution would be to bring more Sunnis into the Hashd, but it will be hard to rebalance a force that consists of some 120,000 Shias and only about 16,000 Sunnis.

Mr Pregent says that the force that eventually goes to Mosul must be mostly Sunni. He argues that it should be recruited from among the American-trained soldiers and officers who were purged from the army by the former prime minister, Nouri al-Maliki. He reckons that there are as many as 50,000 such men, some of them sitting in camps for internally displaced people, who, with an offer of some back pay, would be keen to join up.

Another factor in the battle for Mosul will be the size and role of American forces. Air strikes are a given, but the Pentagon has said that it wants to set up more fire bases of the kind that came under attack last month. Both Ashton Carter, the defence secretary, and General Joe Dunford, the chairman of the joint chiefs of staff, have put forward plans that are believed to include, among other things, the deployment of more special forces and Apache helicopter gunships. These could operate from a new airbase at Erbil, 20 minutes’ flying time from Mosul, if allowed to do so by the Iraqi Kurdistan authorities.

However, the White House has yet to agree. Barack Obama’s pledge of no “boots on the ground” has worn thin, but there is little indication that he is ready to sanction military support on the scale needed to regain Mosul. That may have to wait until the election of a new president—another reason to suppose that Mosul will be in IS hands until next year.

The enemy also gets a vote, at least on the battlefield. Patrick Martin of the Institute for the Study of War, a think-tank in Washington, DC, notes that a recent spate of spectacular suicide-attacks by IS in the south suggests that its strategy is now to destabilise Iraq’s southern provinces, thus putting pressure on the Iraqi army and the Hashd to restrict their operations in the north and west. IS knows that the fall of Mosul will signal, in effect, its defeat in Iraq; so it is determined to delay that moment for as long as it can. It may one day lose its bloody grip on the city. But when, how and at what cost it will be liberated, remains to be seen.

--

No comments:

Post a Comment